In a provocative post about museum games, Kevin Bacon asks the $64k question about applying game mechanics to historical subjects. He observes that military and economic history may be amenable to the same kind of rule-based play that made Launchball such an incredible physics-learning game, but that social history is much harder. In short: “how do you tell the history of the suffragette movement through a video game, without becoming crass?”

It’s a very good question, and the women’s suffrage movement is a particularly good example. A contentious cause whose supporters used bombs, arson and violence to achieve their ends, the achievement of which is now regarded as part of our national narrative of progress (in which we acknowledge the role of those militants, a far cry from the way in which the struggle against the slave trade was presented at the bicentenary of its abolition).

So what kind of games can you make from the struggle for votes for women? The National Archives have a game about the suffragettes as part of their online ‘citizenship’ exhibition. A policeman on a bike waggles his truncheon rather nastily and chases a cyclist with a ‘votes for women’ banner across the screen. The player must answer at speed trivia questions about the battle for suffrage and related human rights advances. Answer enough correctly and the suffragette will escape. Too many wrong answers and the policeman catches her, bicycles colliding in an ugly heap. Crass? Perhaps (it’s certainly dull) but I think I learned something about the role of police violence (as ever) in opposing progressive political movements.

That’s about all I can find online. But it turns out that games about the suffragettes are not as popular now as they were then, if we can stretch the definition of ‘video games’ back to include games-as-popular-culture in the form of Edwardian board and card games. ‘Suffragettes In and Out of Prison‘ is a ‘game and puzzle’ produced in 1908. The player must escape Holloway Gaol through a maze, landing on open doors and escaping both policemen and wardresses who will hinder her bid for freedom. It’s simple, cheap, has basic production values and is highly topical. Perhaps ‘newsgames‘ aren’t such a new idea after all?

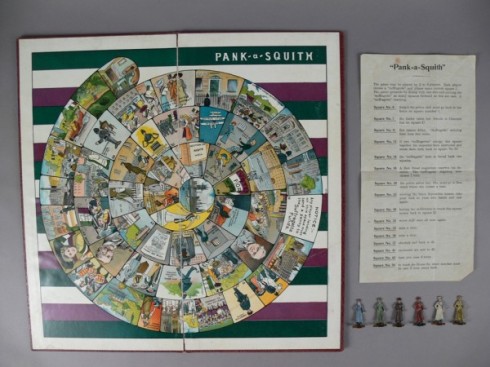

It wasn’t only professional games-makers who sought to make a game of the battle for women’s votes. In 1907, the Kensington branch of the WSPU (the official suffragette movement) produced a card game called ‘the Game of Suffragette‘ with 54 cards in sets featuring both heroes and opponents of the women’s suffrage movement. The ‘Pank-a-Squith‘ board game, produced by the WSPU in 1909, pitted Emmeline Pankhurst against Herbert Asquith, again on a spiral board. This time, progress was made from the outside (‘home’) to the central goal of the House of Parliament, avoiding Holloway along the way.

Many more games and toys were produced by the suffragettes themselves, for propaganda purposes as much as fundraising, and as Kenneth Florey points out, tough “the ostensible justification for their production was to introduce children to the aims of the movement, many of these toys and games actually were aimed at adults” (ain’t it always the way?). So here might also be some of the modern ancestors of our contemporary Games for Change and Persuasive Games.

But merely pointing out that suffragism entered into popular culture, of which games were a part, at the beginning of the twentieth century isn’t to answer Kevin’s key question, which is how engaging with the idea of the suffragettes and their movement might fit into the ‘pleasing feedback loops’ of actual gameplay without appearing to be a crass bolt-on to a generic game. As Martha Henson and I have spent a lot of time saying, making successful engagement games relies on finding a sympathetic entanglement between how the game is played and what it’s trying to get across.

Cataloguing some of the games and toys of the suffrage movement, Elizabeth Crawford talks about “the translation of the mechanics of the women’s suffrage campaign into board and card games”. But what mechanics? The Game of Suffragette could be played in sides. Collected cards equalled points in the form of votes with which a suffrage bill could be passed: politics played as a balance of forces. One could playfully take a political position not necessarily one’s own in the safety of one’s own home.

The key mechanic of the board games seems to be progress. Whether escaping from jail or making your way from the ‘home square’ to the House of Commons, the aim is to propel the suffragette forward to achieve her aim. ‘Progress’ towards democratic equality for women forms part of the narrative of both the WSPU and our own historical understanding of the suffragette movement. The satisfaction of a narrative completed and a goal achieved, is embedded in the game board and rules.

Kevin’s right that it’s hard to make all this work in contemporary video games, which are complex to create and to costly to make, and that ‘smaller, more casual games will struggle’ in games’ overcrowded attention economy. Modern technology might well better be employed in making facsimiles of these Edwardian games via colour reproduction and 3D-printed game pieces than in trying to create new video games about the suffragettes. But I think that finding such a cornucopia of historical gaming culture attached to the suffragette movement, and the creation of both persuasive and commercial games in suffragism’s own moment, suggests that the social history might not be such an outlier when it comes to making games.

Great post, Danny. My comment about a suffragette game was quite off the cuff, and I’d not even Googled to see whether such a thing has ever existed. The contemporary games are a fab discovery.

I agree with you that they certainly anticipate ‘newsgames’, and they demonstrate that games have long worked well as polemic. But whether that translates to history seems doubtful to me, particularly at a time when many in the history / heritage industries are looking to move beyond simple grand narratives.

That said, I would be genuinely delighted to be proven wrong!

Danny – I think your apt observations here, and your discovery of these historical games are a reminder to us that games are not a new way of exploring historical subjects!

I totally agree that applying rules-based game mechanics to historical subjects is a holy grail for cultural institutions. But it seems that the complex worlds created in many commercial role-playing games could be leveraged to explore historical subjects. But yes, these games are very expensive to build. There are a few good examples out there of casual games that do manage to merge the game mechanic with the game’s message, without too much crassness. See for example, eduweb’s “A Sailor’s Life for Me” (http://www.eduweb.com/portfolio/portfolio.php), which uses casual game mechanics to teach about everyday life on an early-19th century tall ship.

I wonder, though, if we are too ambitious in our search for the perfect historical game? Historical subjects and worlds are highly complex, with multiple systems (cultural, economic, political, environmental, etc.) operating in concert. As historians, it is very difficult for us to isolate one system, or one rule, and build a game to teach just that — of course, the results are crass! Casual games are most adept at teaching one, maybe two concepts. So we either need to start approaching history differently (maybe not a bad idea, I think), or start to collaborate with and Activisions, Microsofts, and smaller game companies like That Game Company, out there that are making these complex worlds.