Notes (mostly) from class, Wednesday 11th January 2012.

This term, my final module is ‘Museums and Galleries in the Digital Age’, taught by artist and researcher Nick Lambert. The format looks like it’s going to be quite lecture-driven, and so I’m hazarding a return to blogging to try and process thoughts and ideas coming out of the class.

Week 1’s class and reading was entitled ‘Introducing New Media in Art’, but looked largely at the developments of technology in relationship to art throughout the twentieth century. Individual art movements have their foundational myths: Tristan Tzara at the Cabaret Voltaire, Kosuth’s manifesto, and even Hirst’s Freeze, that posit a rupture with the past, a definitive new way of seeing and making. Not so much with ‘new media art’. While it implicitly begins with the use of computers in fine art in the 1960s, most histories of it tend to look back to the beginning of the 20th century to establish both precedence and continuity for the use of technology in fine art, and in particular to Kinetic and Op(tical) art for aesthetic approaches. In this respect, media art history as a discipline shares something more with academic parvenus like ‘visual culture’ or the ‘digital humanities’ that seek to establish both their necessity and their legitimacy as a focus for research and teaching. The slightly grudgeful tone of Oliver Grau’s introduction to Media Art Histories has something in common with Nicholas Mirzoeff’s to the Visual Culture Reader.

Peter Weibel’s ‘It is Forbidden Not to Touch’ in Grau’s reader makes the case for ‘algorithimic’ art (governed by rules) emerging in Kinetic art and Fluxus both before and contemporaneously with computer-based art. The principles of virtuality, immersive environments and interactivity, all to become core characteristics of computer-driven art had, he argues, been established by kinetic art well before the introduction of the computer itself as an interface. Edward Shanken’s introductory survey in Art and Electronic Media is broad in and light on theory, but similarly makes the case for the manipulation of light (from impressionism onwards) and shape (Duchamp and Gabo) in fine art preceding the use of digital technology.

There’s something slightly recursive about this legitimacy-seeking. ‘New media art’ is considered to have receded from importance in the artworld between the 1960s and the 1990s. (Charlie Gere’s ‘New Media Art and the Gallery in the Digital Age’ is particularly good on this, identifying 1970 as the year in which Jack Burnham’s ‘Software’ at Jewish Museum in NY was followed by Kynaston McShine’s ‘Information’ that set an agenda eschewing the art of systems for the aesthetic of administration). The emergence of net.art, enabled and made accessible by the internet, re-introduced computational art to the art world. Art historians then sought to contextualise it in the history of digital and technological art.

Reading older works about media art, it’s always tempting to see what predictions they ‘got wrong’. Brian Winston’s ‘A Mirror for Brunelleschi’ (1987) [JSTOR£] in fact predicts the development of television though digital to HD fairly accurately. Winston stands against technological determinism, and for social understanding of representational technologies (his explanation of the way in which Technicolor film was effectively a racist technology in Technologies of Seeing still blows my mind a little). In ‘A Mirror…’ Winston offers ‘six slogans’ for artists working with technology that are less timebound:

- A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush – technologies that are prevalent and socially embedded can be more powerful for artists than bleeding edge developments.

- Fear the Greeks – new and more impressive technologies may not prevail in the marketplace

- Festina lente (‘Hurry slowly’) – technological progress is much slower than it seems. Holographs have been in the scientific imagination since 1947.

- Carpe Diem – seize and use whatever technology is available and works

- Fight the good fight – technology does not exist in isolation: use what is socially beneficial

- Horses for courses – don’t let technology master art; use what is appropriate for the project

Theoretical touchstones for the lecture were CP Snow’s ‘Two cultures’ (I’m intrigued by the way i which computer technology sometimes stands in as a proxy for, or as access to the abstract idea of ‘science’); Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (does it or doesn’t it also apply to digital reproduction?) and Marshall McLuhan’s ‘Gutenberg Galaxy’ (communications technology’s impact on our cognition).

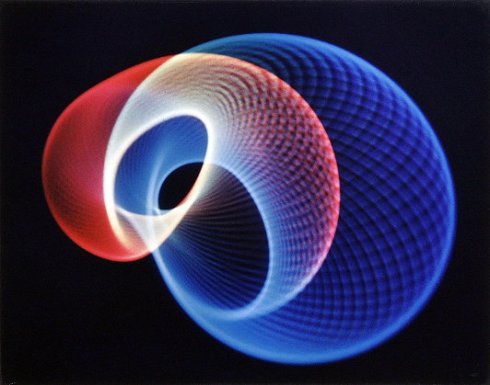

Beyond that, it was an enjoyable romp through some interesting twentieth century avant-garde art. Marrying sound and music was an early impetus: 19th century ‘colour organs’ used musical keyboards to control the generation of light, and Oskar Fischinger sought to manifest ‘visual music’ through the cinematic movement of animated light, as did Mary Ellen Bute, who used oscilloscope images in some of her works. Ben Laposky’s Oscillons, photographs made from waveforms on oscilloscope screens coloured with filters are not only beautiful, but also solve the mystery of where Stereolab acquired their album title. John Whitney crossed the line from using an ‘analogue computer’ used to generate rhythmically precise images on film to pioneering the use of digital images in film. Some kind of ‘virtual space’ is evident in Naum Gabo’s Standing Wave and Alexander Calder’s kinetic mobiles.

Whether this constitutes a convincing pre-history of ‘new media art’, I’m not sure. Personally, much of the moving image stuff I’ve encountered as ‘experimental film’, a form that I’d consider to be still going strong in both black and white cubes. For my money, while given scant attention in many media art pre-histories Len Lye’s work embraces both the kinetic principles of Calder and the visual music of Fischinger and Bute (while also being just more bloody beautiful), but fits less easily into the pre-media art paradigm, partly perhaps because Lye’s underlying philosophy was more humanistic and mystical than algorithmic. When establishing legitimacy with historical precedents, what you exclude can be as telling as what you include.